From LINKS - International Journal of Socialist Renewal

Reviewed by Ben Courtice

From Little Things Big Things Grow: strategies for building revolutionary socialist organisations, by Mick Armstrong, Socialist Alternative, 2007.

As official politics continues to move to the right, a growing gulf is opening up between the hopes and aspirations of millions of working people and the agenda of the ruling capitalist establishment and its parties… Much of the time that disenchantment and discontent finds no outlet, but then it explodes in massive mobilisations like those against the outbreak of the Iraq war in 2003, or the repeated giant rallies against Howard’s WorkChoices.[i]

Thus Mick Armstrong of Socialist Alternative[ii] sets the scene in the introduction to his survey of strategic considerations of how a socialist group should organise. The book opens with the main essay, “The nature and tasks of a socialist propaganda group”. It then proceeds through a series of historical sketches, starting with Marx and Engels and winding its way through various 20th century socialist movements to illustrate the argument he makes in the first chapter.

The core of the argument

Armstrong is clear from the outset that socialist ideas do not have a mass following despite the simmering political discontent we operate in. Locating his group in this situation as a propaganda group (larger than a small discussion circle, smaller than a mass party), he states that “propaganda groups do not have the capacity to lead workers in major struggles and recruit on that basis ... we are primarily arguing our ideas ... not agitating for mass action”. The most he will concede outside of this is that “we can play an important role in initiating some localised struggles and provide some of the key activists in a variety of campaign groups”. Even this is qualified later.

The whole argument is dedicated to this contradiction. Flowing from the passage I quoted at the outset, Armstrong addresses the conflict between the objective needs of the struggle and the abilities he allows his group, which are severely restricted. While the ``challenge today is to rebuild the socialist movement from scratch and breathe life into the union movement and the broader left”, he has already ruled out “agitating for mass action”.

To “rebuild the socialist movement” begins with political clarification. This “vigorous ideological struggle” doesn’t just mean understanding the shortcomings of capitalism, but “a high degree of political demarcation from those on the left who don’t agree with any aspect of Marxism. There can be no compromises, no concessions …” Later in a chapter on the Vietnamese Trotskyists in the 1930s, Armstrong elaborates more on this theme, advocating “the necessity of maintaining a strict political separation between [the Marxists’ own organisation] and those of their rivals on the left” – such rivals including those who “look to the regimes in Vietnam, China, North Korea or Cuba” (never mind the stark differences in each of these countries’ revolutions and current situations!).

Having clarified political points of difference and recruited and steeled a group of cadre in this understanding, the next step in understanding strategy for Armstrong is to identify an audience to whom Marxism can be explained in concrete terms. Armstrong describes this as being able to “answer the central political question: what do we do next?”. He doesn’t say, the question is what the working class, or at least a section of it, should do next, just “we”. This may only be an accidental ambiguity, but it seems the only question to be answered, for Armstrong, is what his small group should do next.

Traditionally, Armstrong explains, the socialist movement has sought to relate to the “vanguard” of the working class, “the most politically conscious” section of it. Yet “there has been no organised political vanguard in any meaningful sense … since the 1970s… Nor are there ongoing campaigns that we can relate to that are radicalising and organising into activity significant bodies of people.” Protests like the Your Rights at Work of that last few years that helped defeat the conservative government of Prime Minister John Howard, or the huge anti-war rallies of 2003 “have not led to the emergence of ongoing organised movements”.

What would constitute an “ongoing organised movement” is not spelt out clearly. The theory that we are in a downturn of political struggle is fashionable from time to time on the left, especially within Armstrong’s political tradition, the International Socialist Tendency of the British Socialist Workers’ Party, which has extensively theorised the idea of the “downturn” ever since the 1980s.

Attendees at Socialist Alternative’s educational seminars may have heard veteran SAlt member Tom O’Lincoln explaining this in terms of the decline in the number of strike days per year, which has set new lows every year for some time. Armstrong’s book is not an assessment of the current political situation, but it’s worth pointing out that the enormous and repeated street protests against Work Choices, albeit led by ALP-aligned union officials[iii], were essentially political strikes and protests on a scale not seen in Australia outside mass upsurges of class struggle. Perhaps this movement (ongoing over several years) is a bit more complicated than the spontaneous and brief outburst of anger that Armstrong sees it as.

A small minority of students

The sole strategic focus for Armstrong is on university students. Armstrong relates some of the obvious things that can be done at university that can’t be done in workplaces, like holding information stalls and club meetings. More fundamentally, he says, workers want an organisation like their unions which can “deliver action”, whereas a propaganda group can’t do that – but a “small minority among students can carry out meaningful activity – hold a lively protest or occupation or initiate a campaign … small groups of socialists can realistically play a leading role and be taken more seriously”. “Meaningful” is here reduced to the Lilliputian scale of “a small minority among students” being the only audience among which socialists, apparently, can be taken seriously. Operating among this most ``meaningful’’ small minority will “help to orient the group away from sectarian abstention”. A “small minority”, one would think, would simply constitute those with immediate prospects for recruitment, raising the question of whether “meaningful activity” is anything more than that which convinces these people to join.

This activity is to be regulated by a “propaganda routine”: regular city and university information stalls, marching en bloc with red flags flying at demonstrations and holding regular branch meetings. Armstrong claims this stops the organisation becoming inward-looking, allowing members to talk to people beyond their ranks who “only agree with some of our arguments”; and it also “keeps the group active”. It almost sounds like an activity schedule for housebound pensioners! But this is a group of overwhelmingly young, energetic students, and hope to be the future revolutionary leadership! The only group that they can work and sound out their ideas with is that “small minority” of students who are interested in working with a revolutionary socialist group. It is not at all clear to this reviewer that this is sufficient to prevent the group “becoming inward-looking”.

The tension identified at the outset of this review, between the organisation’s growth and the needs of the existing workers’ struggle (such as it is), is resolved in favour of the organisation. The role for socialists in movements is entirely subordinated to the organisation’s propaganda routine. When major struggles occur, socialists “have to be able to argue a strategy for winning the struggle, to put forward concrete proposals… They have to draw out the lessons … to point out the role of the police, the media” and so on. Armstrong continues in this very short section on activity in mass struggles: “a propaganda group must be able to link the particular issue … to broader questions such as the capitalists’ neo-liberal agenda, the nature of imperialism.” So despite hoping to offer “concrete proposals” the only real aim of socialists’ involvement is … to explain their broader ideas.

How to get from here to mass struggles?

Can a group with this narrow and exclusive propagandism, only seeking to recruit more people to it’s self-perpetuating propaganda routine, really lead future struggles? The only obstacle Armstrong identifies is that a student-based group “can develop ways of doing things which might seem strange to some blue-collar workers”. But training in arguing for ideas is not the only training you need to lead mass struggles!

It is undoubtedly true that as large a cadre group as possible is needed to effectively lead struggles. That university student politics is a valuable place to recruit activists and begin political training is also undoubtedly true. While socialists remain a small minority, even if we occasionally find ourselves at the head of a demonstration or get a good vote in a particular election, our tasks are indeed of necessity focused on propaganda – defined as explaining our ideas to win more people to them.

On all these topics, the argument put forward in Armstrong’s book is logical, concise and clear. Yet for anyone with experience in mass movements, it must be very frustrating to observe the severe restrictions Armstrong places on what is allowed within his party-building strategy.

The historical sketches that follow the initial exposition are mercenary. It’s OK to only have student members, because parties as great as that of the Polish revolutionaries at the time of the Russian Revolution were started from exclusively student circles. Marxists – Trotskyists, I think he means – must remain utterly separate and on their guard against others, particularly left groups which sympathise with revolutions like Cuba’s, because the Vietnamese Trotskyists let down their guard and were murdered by the Stalinists. One could find all sorts of points to quibble with in these sketches, but since each goes only for a few pages it would be unrealistic to expect a serious historical analysis. They serve as parables to illustrate points of Armstrong’s argument.

In counterposition to the Stalinists, Armstrong defines his political current as those “Marxists whose touchstone is the self-emancipation of the working class”. Self-emancipation of the working class is a noble concept, one that it is hard to argue against. Socialists don’t believe in saviours from on high delivering the workers by individual heroic actions or authoritarian dictates. But Armstrong’s book is not a book about noble principles. It is a book of strategy. What approach do socialists take to the struggle of the working class? The only answer he offers is: build the propaganda group. How do we decide that it’s time to do more than that? When we are a mass party, which Armstrong suggests is “tens of thousands” in the Australian context (a number briefly attained by the Communist Party of Australia at the end of the Second World War, but has never even approached, before or since, by any other socialist group). Certainly in the context of a mass upsurge, the historical sketches illustrate, a small group can grow very rapidly. But the book leaves upsurges to arise spontaneously out of the self-activity of the working class.

The myth of spontaneity

In his famous History of the Russian Revolution, Leon Trotsky described the protests of May 1 1917 thus: “Historians call this movement `spontaneous’ in the conditional sense that no party took the initiative in it.” Quoting a liberal official on the February 1917 revolution, he writes “It is customary to say that the movement began spontaneously, the soldiers themselves went into the street. I cannot at all agree with this. After all, what does the word ‘spontaneously’ mean? ... Spontaneous conception is still more out of place in sociology than in natural science. Owing to the fact that none of the revolutionary leaders with a name was able to hang his label on the movement, it becomes not impersonal but merely nameless.”

And yet Trotsky does document in as much detail as he can the people who called the mass protests of February and May and so on in the Russian Revolution. These people did exist even if their names were never known to history. Trotsky says: “To the question, Who led the February revolution? We can then answer definitely enough: Conscious and tempered workers educated for the most part by the party of Lenin.”

It has been characteristic of sectarian groups to sit on the sidelines and offer advice but never lead, yet declaim “our day will come”. Armstrong provides one of the most clearly explained rationales for this kind of behaviour. In this schema, the masses and the party simply need to wait for the right time. The upsurge will occur some day, and if sufficiently ready, the party will rise to the occasion and provide the revolutionary leadership. A naïve belief in the purely spontaneous uprising of the working class holds this view together.

In Australian left history, there was a saying: if you scratch a strike, you’ll find a red. And that’s not speaking of revolutionary upsurge, merely the elementary organisation of the economic class struggle. Nor is it necessarily speaking of a party that is versed in Trotsky’s writings and organised in a strict, Bolshevist, centralised cadre party: for most of the 20th century, the majority of “reds” were in organisations with great deficiencies – the Industrial Workers of the World with its own worship of spontaneity, the Communist Party of Australia, which unquestioningly took orders from Moscow for most of its existence, and sections of the left-wing of the Australian Labor Party.

If a socialist organisation trains its members well, they will be able to lead from the front when mass discontent turns into mass action. Members must not only be trained only in history and political theory, and in the theory of how and why to build an organisation. To carry through with a revolution, to avoid diversions into reformism that have held back much of the Western left over the last century, does require also a socialist organisation schooled in theory, but if that is all that the socialists build, they will exist in loquacious impotence. You can’t train a pianist by showing them how to build a piano. You can’t train a revolutionary by showing them only how to build a party.

Propaganda and sectarianism

Of course, a pianist without a piano is about as useful as a revolutionary without a party. If the group is very small, it makes perfect sense to determine priorities based on what the group can realistically achieve, and what is needed to grow into a larger group. But growth should not be at any cost and not for its own sake.

The classic definition of sectarianism is pursuing the narrow interests of one’s own party or group ahead of the interests of the class it seeks to represent. It may seem that a party which restricts itself to propaganda for socialism, recruiting but not seriously intervening in struggles, is unlikely to fall into this error. It may be guilty of abstention, but how could it be damaging to the struggle of the working class when it is not really active in it?

An abstentionist regime of propaganda can in fact have a real sectarian impact upon the class struggle. The classic rationale for abstention is that the struggle is at an insufficient stage to intervene in. Yet as we have observed in Trotsky’s classic study of “spontaneous” uprisings and movements, these movements are not “spontaneous” but arise from the initiative of revolutionary-educated, politicised workers at the grassroots. A propaganda group aims to both recruit and train these most politically minded members of the class. If the activity of that propaganda group consists only of building itself, then those activists who are recruited are effectively prevented from playing their natural role, of bringing into being struggles of the working class and its allies.

Let us examine this in a contemporary and practical context. Take the example of the campaign against the Wonthaggi desalination plant in Victoria[iv]. It is an important campaign for the working class to beat back the neoliberal forces privatising basic amenities (water), and to stop the ever-increasing emissions of greenhouse gases that are rapidly bringing the planet’s ecosystems to the point of collapse. To win, this campaign must spread beyond rural Wonthaggi and build support among the working class of Melbourne. One important transmission belt for campaigns and ideas is through students. So in the normal course of events, some more politically aware students become interested in environmental campaigns, and when one such campaign opportunity presents itself, they will take it onto their campus and seek to build the campaign there.

But what would happen if an abstentionist, propagandist socialist group has already joined up most of those politically minded students, and told them not to work on the campaign? The “anti-substitutionism” argument for abstention goes like this: “It isn’t worthwhile because there’s no one else moving on this issue that we can work with to build a broader campaign. It would just be us substituting for such a genuine campaign.” A more blunt assessment -- (to paraphrase) “we don’t think we will recruit anyone by getting involved in that campaign” -- has been reported from Socialist Alternative members in relation to some campus and movement campaign committees in recent years.

If the campaign turned out to have no popular resonance among the student population then a decision to abstain may ultimately be correct, at least in the sense of preserving the group’s energy for some more fruitful activity. However, the criteria commonly used to make such an assessment are too narrow: is there anyone else moving on this campaign we can work with, “partners” or potential recruits? A one-dimensional focus on recruitment, if successful, can strangle such campaigns before they even start. Telling people not to follow their instincts and anger to initiate such a campaign is a dangerous business that can weaken movements from the outset, foster cynicism and lead to a pessimistic “our-time-will-come” passivity in relation to the ongoing crimes of capitalism.

The danger here is not “substitutionism” – if a campaign gathers no support, it doesn’t hurt to drop it as long as the group is clear as to why. In waiting forever for someone else to start moving, the propagandist group acts as a sectarian block to really getting any movement happening, even when the broader population may be desperately needing such a movement.

Socialists who adopt this attitude are always left behind when such movements actually do take off. Waiting for a movement to prove itself big enough and worthy of the socialists’ attention is arrogant. It means that often when the socialist group does realise it ought to be involved, its members are likely to look parasitical and opportunist for jumping on board at such a late stage.

The way out of this dilemma is not to retreat into an abstract routine of propaganda, but to consistently push the boundaries of that routine, to engage wherever possible with forces that are trying to move into action, to develop the movement in whatever small way is possible.

The politics of alliances

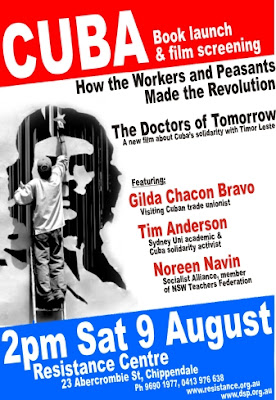

Quoting Cuban Communists probably won’t convince Socialist Alternative’s leaders, who think Cuba is a Stalinist, even capitalist, dictatorship. But despite who may have said it, this quote is relevant to the discussion:

The formula the Communist Party of Cuba proposes for the success of the politics of alliances of the Marxist left is the conception of the alliances as a first step toward convergence, unity, fusion and synthesis of the demands, needs, aspirations and interests of all the oppressed and exploited social class sectors; that is, not as a mere and circumstantial electoral coalition in which the different factions `negotiate’ the exchange of reciprocal support for realising their respective particular interests – something that leads to contradictions over the path to follow, eventually causing the rupture of the alliance – but as the beginning of a strategic process conceived for the long term, of building consensus and elaborating a common program of government that not only confronts but also reverses the consequences of neo-liberalism. The continuation and results of this program would be guaranteed by the broadest and most democratic participation and representation of all those sectors. The organisational forms this process takes would be determined by the conditions in which the struggles of each people unfold, be that of one or various parties, a movement, a front, a coalition or an alliance with which the social revolutionary subject provides itself to undertake this difficult but unavoidable road toward unity. (Jose Ramon Balaguer Cabrera, Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal, #25, January 2004.)

The quote from Armstrong that opened this review provides some of the strategic considerations that ought to back a politics which is not only interventionist, in the sense that it seeks to push forward and strengthen the collective struggles of the working class, but that seeks alliances between different groups, different sectors of society, not just narrowly the organised working class (let alone just the next prospective recruits). The advances of neoliberalism have had a big impact on the class struggle since the 1960s, the last era considered in Armstrong’s series of historical lessons.

The 1960s

In the 1960s, the revolutionary left groups were not only small but were isolated by the strength of the reformist left in the official communist and social-democratic parties, they were shut out from organised working-class politics at every opportunity. Further, the “long boom” following the Second World War created a period of stability which gave rise to conservatism in the working class, a second barrier to radicals finding a foothold. This meant that although many revolutionary groups were able to grow quickly during the tumultuous events of 1968 and subsequent years, they maintained a highly propagandistic and factionalised outlook in opposition to the reformists who were blocking them (and unfortunately toward other revolutionary left currents as well). In the case of the Trotskyist left, this attitude has persisted (somewhat understandably) since the current foundation as a small minority in opposition to Stalinism within the communist movement.

Armstrong notes the absence today of large reformist organisations for the revolutionary left to look to for recruits and debate, but does not recognise the other conclusions that follow from this. He also notes the gulf “between the hopes and aspirations of millions of working people and the agenda of the ruling capitalist establishment and its parties”, but fails to see the potential for initiating struggles against the establishment (as we have discussed above).

The absence of large reformist organisations is not simply coincidence. The neoliberal ideology of modern capitalism does not want to allow space for liberal reforms, and the pro-capitalist reformist parties have been squeezed out (like most of the Eurocommunist current of communist parties) or transformed into explicitly neoliberal parties (such as the social-democratic and labour parties).

`Broad left’ parties rejected

Armstrong’s last chapter, “Is there an easier road?”, addresses the possibility of “broad left” parties and alliances and rejects them. Arguing against Scottish socialist Murray Smith, an advocate of broad left parties such as the Scottish Socialist Party, Armstrong says Smith ``fudges the whole question of reform versus revolutionary politics, arguing that in current political circumstances it is not necessary to build clear-cut revolutionary parties because `the social democratic parties and to a very large extent the Communist parties are finished as vehicles for working class aspirations’’’. Armstrong argues that “organised reformism is not simply based on parties like the ALP, but even more importantly on the trade union bureaucracy.”

Yet this leaves out the possibility of alliances with others who are not reformists, and those who are new to politics and are fighting for reform. Who is a reformist today, anyway? Hugo Chavez, who is fighting for his rather revolutionary agenda through official bodies and elections? Unionists and community activists who fight for reforms? The fact that reforms now have to be fought for at the grassroots (and are rarely won) even in the imperialist heartlands, and are no longer delivered as a pacifier by social-democratic governments, changes the emphasis on reform for the revolutionary movement.

Reforms and revolution

Rosa Luxemburg in the introduction to her famous article Reform or Revolution opens with the question: “Can the social democracy [Communists] be against reforms? Can we counterpose the social revolution, the transformation of the existing order, our final goal, to social reforms? Certainly not. The daily struggle for reforms, for the amelioration of the condition of the workers within the framework of the existing social order, and for democratic institutions, offers to the social democracy the only means of engaging in the proletarian class war and working in the direction of the final goal – the conquest of political power…”

Luxemburg’s polemical opponent, German reformist Eduard Bernstein, summed up his argument for disconnecting reform and revolution with the slogan: “The final goal, no matter what it is, is nothing; the movement is everything.” This is about as “profound” as saying that the means justifies the end! It’s only sensible meaning is that the movement, unconsciously, maybe even accidentally, will itself lead to socialism. This is a version of the socialism-is-inevitable school of thought, which sadly does not seem to be correct. Movements for reform are easily subject to cooption, narrow sectoralism and are compatible with capitalism. Just having a movement in itself guarantees nothing.

If we are to be practical about things, however, we do need a movement. To disagree with Bernstein’s slogan does not mean to agree with it’s inverse, “The movement, no matter what it is about, is nothing; the final goal is everything”. As Luxemburg puts it, “Between social reforms and revolution there exists for the social democracy an indissoluble tie. The struggle for reforms is its means; the social revolution, its aim.”

The process of building the Socialist Alliance in Australia and in England has been a central debate over alliance strategy in the English-speaking left. It has provoked serious divides in left organisations that have tried these forms of alliance. Ironically, the cause of unity can cause division! But some disagreement is inevitable when new ideas are tried out.

Most of the left went into the Socialist Alliance process in Australia with a genuine openness to see how it would work, but with little idea of how or why it should work (although Socialist Alternative left after only a few months, having barely participated at all). The International Socialist Tendency (in Australia, the International Socialist Organisation) formulated the idea that the Socialist Alliance was a “united front of a special type” to work with those breaking to the left of social-democratic parties like the ALP. Yet many in the Socialist Alliance were people of the left who had abandoned the ALP long before. The tactical alliance suggested by the “united front of a special type” tactic was misplaced. Strategic and longer term unity is what the process should have aimed for: to unite those socialists who find themselves fighting the same struggle, now, against neoliberalism. People who had no confidence in this unity, or in the possibility of struggle against neoliberalism, were inevitably confused, demoralised and disappointed. Hence the period of confusion following the initial foray into alliance politics.

Alliances of the Marxist left organiations (to start with) can take many forms, and progress through many stages. Some (like Socialist Alternative) sadly are unlikely to travel along this road anytime soon. Yet to make the necessary alliances with new protest movements that appear, being able to unite the activist, interventionist Marxist left is likely to be a prerequisite. Serious movements will demand it of us. Indeed, serious movement activism requires all manner of tactical and strategic alliance building.

Who’s afraid of Socialist Alternative?

A leading member of the Democratic Socialist Perspective in the Socialist Alliance once wrote a private discussion paper entitled “Who’s afraid of Socialist Alternative” that was subsequently leaked and made public. Both it and these writings of Mick Armstrong may well end up a footnote in the history of the Australian left if Socialist Alternative’s politics are ultimately as frustratingly impotent as this review would suggest. But in fact, there are those who worry are afraid.

Socialist Alternative have experienced growth among university students and become the second-largest socialist organisation in Australia today. Its size on some campuses is sufficient to effectively monopolise the space with its brand of socialist politics. This certainly causes some on the left great frustration. Should Socialist Alternative’s methods be copied? Perhaps we, too, ought to revert to a more simple propaganda routine? These nagging doubts need to be answered, and it is hoped that this review will achieve this in part.

Most movement work that Socialist Alternative engages in currently is sporadically building protest rallies initiated by others, quite genuinely, but whether this is out of a real expectation that it can make a difference is uncertain: it seems more it is angling for recruits. Certainly, Socialist Alternative is effective in recruiting. Their members work hard at it, unlike many of its detractors, which along with its single-mindedness is probably the real reason for Socialist Alternative’s modest growth, not any magic property of its propaganda routine. If its propaganda routine were more successful, it would have more impact on other left groups, but typically its membership remains quite separate and barely engages in conversation with the rest of the left.

All this shows that Socialist Alternative’s superficially magic bullet of a narrow propaganda routine is in fact very shaky. It would be good if Socialist Alternative could regain some confidence in the class struggle and direct its members to do serious work building and initiating campaigns. Issues arise regularly in Australian politics, which shake the working class’ confidence in the system. Organised initiatives to try out protest action and movement campaign building on these issues can move the struggle forward with enough pushing. We don’t need to wait for tens of thousands of members: the left can have a serious impact now if it is organised to do so, and it is sad that Socialist Alternative keep their youthful, energetic membership isolated from almost all such activity.

{Ben Courtice is a member of the Democratic Socialist Perspective, a Marxist tendency within the Socialist Alliance of Australia. ]

Notes [i] Australia’s previous Prime Minister John Howard introduced a series of laws (``WorkChoices’’) to restrict workers’ rights to organise and give employers more power. Hundreds of thousands of workers protested in the streets around Australia throughout 2006-7, organised by the trade union movement under the banner of “Your Rights at Work”.

[ii] Socialist Alternative (http://sa.org.au/) were founded by activists expelled from the International Socialist Organisation (now known as Solidarity) in 1995. Both groups are from the International Socialist Tendency (IST) tradition founded by British Marxist Tony Cliff.

[iii] The Australian Labor Party (ALP), Australia’s current governing party, is a social-democratic party with institutional links to the unions, like the British Labour Party. In the 1980s, an ALP government pursued a social contract with the unions which demobilised rank and file union organisation and saw a decline in living standards. Since then the ALP has increasingly followed an openly neoliberal agenda.

[iv] The ALP government of the south-eastern Australian state of Victoria plans to augment the water supply by constructing a massive desalination plant near the coastal town of Wonthaggi. This is controversial because domestic water bills are likely to increase up to five times over to pay for the construction, and the plant will cause a great amount of pollution both locally and from the large amount of power generation necessary to operate it.